Manu: From Grief to Glory

When Arsene Wenger signed a little-known left-back from AS Monaco on 17th June 1997, no-one really batted an eyelid, except perhaps to comment upon the new player's flowing blonde locks, the sartorial elegance of his pastel blue suit and the fact that "its another Frenchman".

Given the fact that he was paraded to the British press at the same time as another new signing - renowned Dutch winger Marc Overmars - this was not particularly surprising. Little did anyone reading press articles announcing the signings on June 18th 1997 realise the impact that would be made by the lesser-known of the two new players. It is fair to say that the Frenchman was a relative unknown back then, and yet one calendar year and one World Cup later, there would be few people across the world that would not recognise him or know his name.

As a 12-year-old schoolboy in Normandy, Emmanuel Petit began to show outstanding strength and poise on the ball and was soon to be selected for the region and the national under 13 team, the first steps on the ladder to domestic and international success. However, something then happened to the young Petit that would affect his life forever. Whilst on the pitch and playing for his club near the Petit family's hometown of Dieppe, Manu's brother Olivier collapsed and died from a blood clot on the brain. As he fought to come to terms with the loss of his older brother and hero, the younger Emmanuel almost gave up the game. Football, however strongly Bill Shankly might have disagreed, was certainly not more important than life and death for Manu.

To this day, before each game he plays - including the World Cup and FA Cup Finals - Manu would stand in the penalty area ahead of the left post. He will then pull up a blade of grass and cast his eyes toward the skies to see if his brother looks at him, then the grass is thrown to the wind in silent remembrance. When the referee is about to blow his whistle for kick-off, he hits his forehead and shin-pad. It's almost an instinctive thing, not a silly superstition. That he still plays football after the trauma he went through is testament not only to his sense of self-worth, but also his determination to succeed - not only for him, but also for Olivier.

The death of Olivier radically changed Manu. He went off the rails, he was married and divorced. His wild nights on the French Riviera became the stuff of legend. Now, Petit says "I don't want to talk about the things I did because I am ashamed of them. Because of what happened to Olivier, my character changed for the worse. I became very aggressive and had no friends. I couldn't be bothered to do anything. I hated everything to do with football. I was playing for Monaco and was in the national team at 18, but couldn't see the point of training to be a footballer because it had killed my brother. I thought about leaving football but I remembered Olivier and knew he wouldn't want me to do that".

Two things helped turn a life of debauchery and underachievement into one of medal-winning glory: a book one of Petit's friends gave him, and the help of Arsene Wenger. The book was a French translation of The Celestine Prophecy by James Redfield - a spiritual road movie of a tale that became Petit's Catcher in the Rye. It provided the understanding he needed to turn things around. "I had to look into the deepest part of my soul - it helped things make sense to me; what had happened and what should happen next. I found my doctor in that book."

It was Wenger who had first brought Petit from Normandy to the swish Mediterranean principality of Monaco on the recommendation of Pierre Tournier, who ran the club's centre of excellence. Two years later, as a 17-year-old, Petit made his debut - as a left-back. Off the pitch, however, Petit suffered from perpetual mood swings, partly as a result of the death of his brother. "It was definitely a big problem for him," said Wenger. "He was profoundly affected and almost quit the game."

Wenger was instrumental in restoring the player's relationship with his parents - something that had been stretched to breaking point by the tragedy. He tried to understand the extent of their son's turmoil, then put in the hours to bring him back from the brink. Eveline and Jean-Paul Petit's gratitude is a matter of record. All parties describe the relationship with Wenger as "older brother to younger brother, not father to son". Unlike many managers, Wenger took time to understand Manu, to understand his psychology. He spent many hours talking to him and understood what Petit could and could not do. Later, Petit stated that everything he has won in his career is down to Arsene, who he has called "the greatest man I know."

This bond between the two led to the move to Highbury for 2.5m pounds in the summer of 1997, ostensibly as left-back reserve to the evergreen Nigel Winterburn. When he first arrived in north London, the glitzy playground of the rich and famous he had left behind seemed a million miles away. A slightly inauspicious start - playing in central midfield - led to bouts of homesickness and feelings that, in Petit's own words "I thought I had made a mistake and you could have offered me a million pounds to stay and I would have turned it down."

Yet within the space of a few months, he was being hailed as one half of the finest midfield partnerships Arsenal and English football has ever seen, alongside his friend and compatriot Patrick Vieira.

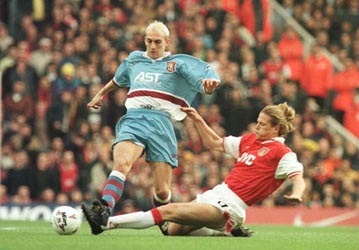

This burgeoning partnership was the fulcrum behind Arsenal's magical Double season of 1997-98. Initial troubles and splits within the camp were put right at a team meeting following a home defeat against Blackburn in December 1997. The divisions between the French and English players within the squad were ironed out and Petit and Vieira were briefed with forming a defensive wall in front of the ageing back four, thus providing them with the necessary protection. At the same time, they were instructed to use their creativity to launch attacks via the wingers Parlour and Overmars. Wenger put Petit's ethic of tirelessly looking for work, seeking the ball and releasing other players to the test. It was one he passed with flying colours. Aime Jacquet would later look for him to do the same.

This tactical masterstroke by Wenger drove Arsenal to the title ahead of Man United, and to win The Double by defeating Newcastle United 2-0 in the FA Cup Final at Wembley. On the way to the League and Cup, Petit scored only two goals but one was critical. Needing to win against Derby in the League, the talismanic Dennis Bergkamp had seen a penalty saved and then had limped off injured. The team and the crowd looked for a hero. Petit slammed home a 25-yard daisycutter and as he celebrated, Highbury exploded. 1-0, a crucial result and the hero worship began.

Petit also had a major part to play in the Cup Final where he'll be long remembered for a peach of a pass, floated through with his trusty left foot, that put Marc Overmars away to score our opening goal. As Petit danced away in a fan's jester hat on the Wembley turf following the Cup Final, he was no doubt thinking that things couldn't possibly get any better. And yet, the rise to fame and glory was far from over . . . .

Selected in the French squad for World Cup '98 along with team-mate Vieira, his performances were simply outstanding. During the tournament Manu went from squad player to the first-choice central midfielder of French boss Jacquet. His two wickedly curling first-half corners in the final against Brazil were converted by Zinedine Zidane, and then came the piece de resistance. In the last minute, put through by his friend Vieira, Petit outpaced the Brazilian defence and slid the ball past Taffarel into the net. 3-0, France had defeated Brazil and won the World Cup in Paris, and that third goal on July 12th 1998 in the Stade de France was the perfect catharsis for Manu. As ever, he later dedicated that goal to Olivier at the numerous press conferences he had to attend - the price of his new-found global fame.